Survivor: Singapore

Stupid Singapore. I'm sorry it's been so long since I disappeared.

Stupid Singapore. I'm sorry it's been so long since I disappeared.Seven months ago I was in the mountains of B.C., sitting in the family pickup with the engine off, alone. It was a late-December night, the kind where you need the heater on to hold the steering wheel with bare hands. I'd just pulled onto a little rope ferry that services the far side of a lake up there, and all I could see outside was yellow and black safety striping, a wall of it, grotty from rust and highway snow, inches from my front bumper: the back end of a dump truck hired to spread sand on remote icy roads. I was late for a 49th-anniversary party at the village on the other side. I sat there and engraved the moment on my mind: the world reduced to my vehicle, the seeping cold outside the doors, the dark waters slipping by beneath me, the striped warning that filled my view. Beyond a doubt: I was heading somewhere new.

A few days later I was stepping over soggy winter leaves on the sidewalks in Vancouver, with a ticket to Asia in my backpack, laughing with friends that I must be getting nearer because the election signs were already half in Chinese. My girlfriend Mel was in Singapore, helping an NGO set up a new university for needy Asian women, but getting bummed out because her little South Seas island-state is a glittering, bazillion-dollar shipping and finance hub that tends to send any fellow dreamers running for the hills. The idea was: fly over, get a job, then keep up her confidence about saving the world.

I've painted myself as a hero on my other trips, the one going out and doing good, but this time the spotlight was squarely on Mel. She was hopping all over the continent, doing tête-à-têtes with refugee leaders, wining and dining nobility and CEOs. As soon as I stepped off the plane into a muggy January heat, I was meeting the biggest names in town too – but as a self-styled supporting player, and the cameras don't dwell on supporting players. Some highlights from my first few weeks:

January 12 – George Soros swung through to speak to the business community (a ripple went through the crowd when a college upstart asked him if Singapore was an open society – the next day's papers acted indignant at his negative reply). Melanie was pointing out all the people she knew, among them the MC, a family friend and former UN ambassador who'd advised her to join the Foreign Service like a sensible girl instead of tramping off with her NGO. She wanted to avoid him at all costs. He ran into us in the lobby and briskly shook my hand before Melanie could steer us to the next exit out.

January 17 – I went bungee jumping for the national paper (Singapore booted the British out in the 60s, but kept the English language so the remaining Chinese could still communicate with others on and off the island). Just a short promotional piece, but a pretty good start off the blocks. When I handed it in, I found out my editor had quit, and five months later they're still sitting on it. Plus, supporting characters don't seem to get paid.

January 24 – I interviewed for a job at the national university, as a copywriter to help them beg rich people for money. They kept insisting they wanted me, but then they'd never call back to seal the deal. This dragged on for a month, at which point Mel and I spotted the head of the office at a forum on political prisoners. As late as the 80s, Singapore was throwing its communist sympathizers in jail for as long as they liked, and this was the first time anyone had dared discuss it in public. It was a hero thing [1] to support an event that seemed designed to spark the government's ire: one of the speakers cancelled at the last minute, and everyone was looking over their shoulders trying to guess who the government spies might be. It turns out my prospective boss had been a political prisoner himself. For different reasons, we were equally uneasy to see each other.

Other uncomfortable encounters over the months: I got a callback at a multinational ad agency, and everything was going fine until I insulted Indonesia's official tourist slogan, which my interviewer turned out to have written himself. Mel and I dogsat for an aunt of hers one weekend, which was fun because she lives in a colonial mansion with two floors of private library, but which was less fun because it smelled like tropical dog pee from the moment we stepped in the door. There've been interesting kids on the fringes: Malay TV and music producers, or a South Indian intellectual who got sidelined into a career with the K9 squad after a lovesick year threw him off the academic track. Our plans have had a hard time sticking. You start to see a pattern. You start to get the impression that Singapore doesn't want to be seduced by you.

I want to seduce every place I see. I want every latitude and longitude to fall head over heels in love with me. Seduction craves what's illicit – foreign – yes, but there's a catch: the thing also has to be just enough the same as you. It can't be so different that it doesn't want to be seduced in return.

Salvador was a place that seduced you back, move for move: deeply different but deeply recognizable, deeply eager to fold you in its strange embrace. At the end of my last trip there, a year ago almost exactly, I dropped by the crack alley bar whose owner had given me shelter when it rained: I gave her a copy of the painting I'd done next door, asked how business was doing. When she said she didn't know how she'd pay next month's rent, I gave her a sprig of herb that wards against misfortune. An early-morning client looked up from his beer, and said, "You look like a tourist, but you aren't one, are you." I said of course I was, and he pressed two tangerines into my hands for breakfast.

The seduction there, in any sense that I could imagine, was eerily complete: intimate enough to shake the walls, if not break them down entirely. By comparison, Singapore doesn't seem remotely as interested in what's on offer from the blue-eyed and ash-blond. It's already gotten what suits it, and how – Singapore English with its grace notes of Chinese and Malay; local chicken-rice dishes eaten with traditional fork and (why?) spoon; packed cineplexes playing censored Hollywood blockbusters ("shit" is okay on TV, "bitch" isn't on film) – but the "expat packages" that used to entice Western businesspeople with inflated wages and cushy apartments don't get doled out much anymore. The old Chinese uncles selling roadside ice cream don't acknowledge you when you stop to ask for directions.

So for six long months Mel's mother put me up at her house, plying me with all-I could-eat fisheye soup and long-haired fruits (or laughingly serving roast lamb and mint jelly to please me, because she studied law in London and is as in on the East–West joke as anybody), while I poked around for a job that never materialized, designed a few T-shirts but painted nothing that mattered, idled my time learning to dive in the condominium pool, and that was all. I helped Mel do a PowerPoint that she sent off to Japan, but I don't know how inspiring I was. With no stories of seduction, I have nothing to report.

Mel and I read together a lot. Curled up on the couch or at bus stops, we fell in love with The Wind-up Bird Chronicle, by Haruki Murakami. The story loomed like prophecy to me: the man who pored over encyclopedias as a little boy; the jobless professional set adrift in modern Asia; the cockeyed sexuality; the quiet, killing passages like this one here:

"I took a blouse and skirt of Kumiko's to the cleaner's by the station … wearing a pair of thin green cotton pants, my usual tennis shoes, and the yellow Van Halen promotional T-shirt … I saw lots of men my age, but not one of them wore a

Van Halen T-shirt. Each wore his company's lapel pin and clutched a copy of the

Nikkei News under his arm. The bell rang, and a number of them dashed up the

stairs. I hadn't seen men like this for a long time."

I clung to that language. If I listened closely enough to it, I felt, I might learn to see in my limbo not a string of failures, but a difficult beauty I'd never fathomed before: is this what you see through the eyes of a supporting player? When I first visited the tropics, every sight was strange to me – palm trees looked animal, their fallen bark like leather, fallen fronds like rib cages, leafstalks like disarticulated bones – but I wouldn't ever stand by what I saw, because I had no idea what the local stars saw in those same things. As for the narrator in The Wind-Up Bird – he could care less what anyone else thinks they know, so long as he has one other person to be an outsider with him. From his window, he hears "the mechanical cry of a bird that sounded as if it were winding a spring. We called it the wind-up bird. Kumiko gave it the name … Every day it would come to the stand of trees in our neighborhood and wind the spring of our quiet little world."

An unseen bird sang outside my window, too, but it drove me nuts – because nobody in this whole place could share its name with me. I'd imitate it for anyone I met: "Sort of a HOO-ah, HOO-ah, HOO-ah." One schoolteacher laughed and said her kids imitate it to bug her, but she didn't have any idea what it was, or what it looked like. The only guesses I got came from other foreigners: one Australian woman thought it might be a curlew (it wasn't); the family's Filipina housekeeper said it was a black bird, with bright red eyes.

Singapore proudly calls itself a "garden city," its expressways carving through a forest of spreading raintrees, its overpasses trellised with vines, but the garden must be tended by a secret gardening cabal, because no native Singaporean seems to associate with the nature around them. Most people who bring their kids to the sprawling Botanic Gardens are Europeans of one stripe or another, and maids from poorer nearby islands are the only ones who eat their lunch on the miraculous downtown greens, where spinning pairs of dragonflies flash red in the sunlight, and mimosa leaves fold up as your foot brushes by. In Canada, trees are an invitation: you expect to see trails snaking into them, a mountain to climb on the other side, hills to sled on. Here, you treat anything green as impenetrable: wide hedges prevent jaywalking; people stay away from a block of towering jungle behind the shopping district saying it used to be full of stray dogs. My double in the Wind-Up Bird was one step ahead of me. The name of that unseen bird is important, but don't look to a modern metropolis for what it's called. Any private name will be better.

In the novel, a psychic war vet tells the narrator not to fight the "flow": "When you're supposed to go down, find the deepest well and go down to the bottom. When there's no flow, stay still." Then, he warns him against water in general: "Sometime in the future, this young fellow could experience real suffering in connection with water. Water that's missing from where it's supposed to be. Water that's present where it's not supposed to be." Singapore's drains and gutters run aboveground, crisscrossing fields like a baby born with its blood vessels on the outside. If you follow the drainway from our condo, it joins with progressively larger longkang – canals – until in a few hours' walk it empties as the Singapore River into the old seaside port. There, the original Malay-speaking "sea gypsies" (classy) were squeezed out by Chinese coolies (opium-smoking men, square-hatted construction-worker women), who in turn gave way to (this is where you come in) sunburnt Danes with their arms around dark-haired, not-quite-Singaporean girls. Today, the eyes painted on the riverboat prows are there for tourists rather than water demons; Ma Cho Po, the Goddess of the Sea, is a museum curiosity; the fine old dockfront buildings are bars with $30 drinks and plush seats.

I go down there when we go out. On weekday afternoons when I need something nicer to look at, I hang around the top of the canal instead. Right behind our building is a different, pocket world: the bridge across the longkang is a few teetering planks, and from them you can watch schools of little fish swimming around in the runoff below you. The other day, Mel's sister found a four-foot monitor lizard sunning itself halfway across. Farther on the other side are the colossal housing projects that cover the heart of the island – home to four of every five Singaporeans. Just here, though, a project has been taken down, leaving an expanse of fallow grass, a few tall trees, and a half-built church. The government is still deciding what to do with this place. At the base of the trees are familiar offerings of dead chickens and incense: these are Taoist, left by the local psychic war vets. A few people walk dogs in the evening. Inside a gazebo a junior high school girl has scrawled a few hieroglyphs, along with the words: "Zillah love Zaimi and hate him."

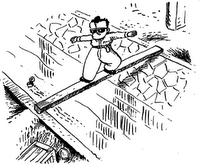

To see a place like this, with strange messages and overgrown life, you might ordinarily have to cross the strait to Malaysia, where I suspect people know what that bird is called. The picture I've attached is by a Malaysian cartoonist, Lat, loved for his portrayals of rural Malaysia today – and Singapore's past. That is me and my longkang. When I'm out there, I feel like all of civilization is suspended on a drop of water, shivering, just holding on.

The longkang first appears from under our street, flowing out from a dark concrete tunnel that, on dry days, is big enough to walk into if you swing over the safety rail and stoop. Wind-Up Bird taught me what a jobless non-hero does, at least: he goes down a well and concentrates until he hallucinates his triumph. In mid March, Mel took off on a week-long trip to Bangladesh, and the darkness got to be too much for me. I grabbed a headlamp and went in. A few paces inside, the tunnel took a right, and then a left. Pitch black. Faint trickles of light from the roadside drains above. I edged forward, swiveling my light around me. Storm waters must scrub the culvert clean: this is the tropics, but there was no moss, there were no plate-sized spiders, just blank concrete walls, and sudden night. I had to crouch lower as I reached what must be the end of our road, and still lower after another left. Manhole covers clanged throughout the shaft when people passed by. Then, I reached the end: through a pinhole of light, I could see where the stream first dips underground. Another street. There was nothing to report.

When I got back to the surface, I found out I had a fever – because it broke all over me, at once.

Melanie came back from Bangladesh shaking her head at the tea barons she'd been meeting, and their tea baron ways. She'd seen village courts there too, sat with the crowds of women, and she'd decided grandiose university projects weren't enough on their own. She wanted to get involved in something on the ground, and I could do it with her. I went underground on April 19. By April 30, I was by her side on a new ferry, crossing over to Indonesia to track down a human trafficking NGO.

Here's what I've found out: In at least one case, when a Malaysian man looks at a fallen palm frond, what he actually sees is a toy that his friends used to pull each other around on when he was small, and he wishes he could pull his own son the same way, even though nobody remembers that game in modern Kuala Lumpur. That I know from Lat, because he put it at the end of one of his comics. The bird I heard is a koel – a cuckoo that looks like a crow with bright red eyes. That I know from the signs at a mangrove reserve on Singapore's north shore, which also had mudskippers and tree crabs and sand lobsters that make giant termite nests in the muck. I found out I had a job, finally. That I know from the stupid bureaucracy at the national university.

And I know that by pegging all my hopes on becoming a salary man, I was doing someone or something a hell of a disservice. You don't seduce anything by self-domesticating yourself, no matter what the place might be like. You make people fall in love with you, and damn the consequences. So: here I am, here I am, and I hope you're all well.

Indonesian men were smoking on deck as our ferry cut south across the Singapore Strait. Zillah love Zaimi, and hate him: beyond a doubt I was heading somewhere new.

Actually you can tell you're getting closer to Singapore because during election season you see hardly any election signs at all,

President Nathan

[1] In one of his poems, this Singapore writer named Alfian Sa'at tells how his friend "did a hero thing," or what passes for one here: on a multiple-choice test from the government, he courageously penciled in nothing but As.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home